Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

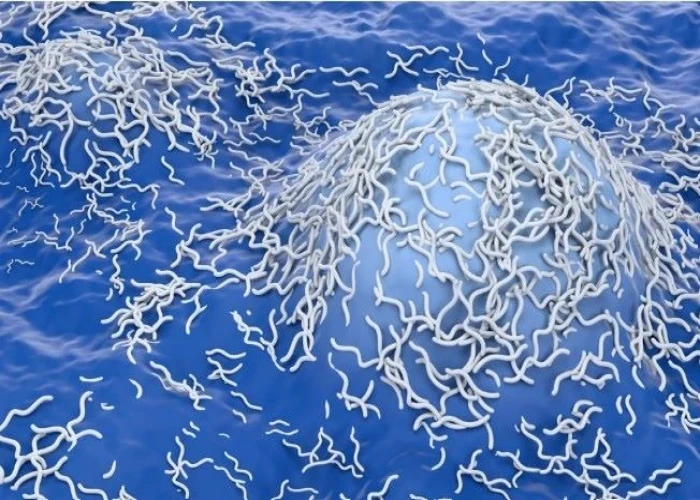

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastoma is a type of cancer that develops from immature nerve cells found in several areas of the body, most commonly in the adrenal glands (located above the kidneys) but also in the chest, neck, or pelvis. It is most often diagnosed in young children, typically under the age of 5.

Symptoms of neuroblastoma may include a lump or swelling in the abdomen, chest, neck or pelvis, bone pain, and unexplained weight loss. In some cases, the cancer may produce hormones that cause symptoms such as high blood pressure, rapid heartbeat, and flushing.

Diagnosis of neuroblastoma may involve a physical exam, blood tests, imaging studies such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRI scans, and a biopsy to confirm the presence of cancer cells.

Treatment options for neuroblastoma may depend on the stage and location of the cancer, as well as the age and overall health of the patient. Options may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and bone marrow transplantation. A combination of treatments may be used to achieve the best outcome.

Prognosis for neuroblastoma depends on the stage and location of the cancer, as well as the age and overall health of the patient. In some cases, neuroblastoma may resolve on its own, while in other cases it may require aggressive treatment. It is important to work closely with your healthcare team to develop a treatment plan that is tailored to your individual needs and circumstances.

Research into new treatments and therapies for neuroblastoma is ongoing, and early detection and treatment can improve outcomes for those affected by this condition.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Abdomen pain

- Changes to the eyes, including drooping eyelids and unequal pupil size

- Changes in bowel habits, such as diarrhea or constipation

- Bone pain

- Weight loss

- Fever

- Back pain

- Chest pain

- Diarrhea

- Swollen lump or skin nodules

- Eyeballs that seem to protrude from the sockets (proptosis)

Disease Causes

Neuroblastoma

In general, cancer begins with a genetic mutation that allows normal, healthy cells to continue growing without responding to the signals to stop, which normal cells do. Cancer cells grow and multiply out of control. The accumulating abnormal cells form a mass (tumor).

Neuroblastoma begins in neuroblasts — immature nerve cells that a fetus makes as part of its development process.

As the fetus matures, neuroblasts eventually turn into nerve cells and fibers and the cells that make up the adrenal glands. Most neuroblasts mature by birth, though a small number of immature neuroblasts can be found in newborns. In most cases, these neuroblasts mature or disappear. Others, however, form a tumor — a neuroblastoma.

It isn't clear what causes the initial genetic mutation that leads to neuroblastoma.

Disease Prevents

Disease Treatments

Your child's doctor selects a treatment plan based on several factors that affect your child's prognosis. Factors include your child's age, the stage of the cancer, the type of cells involved in the cancer, and whether there are any abnormalities in the chromosomes and genes.

Your child's doctor uses this information to categorize the cancer as low risk, intermediate risk or high risk. What treatment or combination of treatments your child receives for neuroblastoma depends on the risk category.

Surgery

Surgeons use scalpels and other surgical tools to remove cancer cells. In children with low-risk neuroblastoma, surgery to remove the tumor may be the only treatment needed.

Whether the tumor can be completely removed depends on its location and its size. Tumors that are attached to nearby vital organs — such as the lungs or the spinal cord — may be too risky to remove.

In intermediate-risk and high-risk neuroblastoma, surgeons may try to remove as much of the tumor as possible. Other treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation, may then be used to kill remaining cancer cells.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses chemicals to destroy cancer cells. Chemotherapy targets rapidly growing cells in the body, including cancer cells. Unfortunately, chemotherapy also damages healthy cells that grow quickly, such as cells in the hair follicles and in the gastrointestinal system, which can cause side effects.

Children with intermediate-risk neuroblastoma often receive a combination of chemotherapy drugs before surgery to improve the chances that the entire tumor can be removed.

Children with high-risk neuroblastoma usually receive high doses of chemotherapy drugs to shrink the tumor and to kill any cancer cells that have spread elsewhere in the body. Chemotherapy is usually used before surgery and before bone marrow transplant.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams, such as X-rays, to destroy cancer cells.

Children with low-risk or intermediate-risk neuroblastoma may receive radiation therapy if surgery and chemotherapy haven't been helpful. Children with high-risk neuroblastoma may receive radiation therapy after chemotherapy and surgery, to prevent cancer from recurring.

Radiation therapy primarily affects the area where it's aimed, but some healthy cells may be damaged by the radiation. What side effects your child experiences depends on where the radiation is directed and how much radiation is administered.

Bone marrow transplant

Children with high-risk neuroblastoma may receive a transplant using stem cells collected from bone marrow (autologous stem cell transplant).

Before the bone marrow transplant, also known as stem cell transplant, your child undergoes a procedure that filters and collects stem cells from his or her blood. The stem cells are stored for later use. Then high doses of chemotherapy are used to kill any remaining cancer cells in your child's body. Your child's stem cells are then injected into your child's body, where they can form new, healthy blood cells.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses drugs that work by signaling your body's immune system to help fight cancer cells. Children with high-risk neuroblastoma may receive immunotherapy drugs that stimulate the immune system to kill the neuroblastoma cells.

Newer treatments

Doctors are studying a newer form of radiation therapy that may help control high-risk neuroblastoma. The treatment uses a radioactive form of the chemical metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG). When injected in to the bloodstream, the MIBG travels to the neuroblastoma cells and releases the radiation.

MIBG therapy is sometimes combined with chemotherapy or bone marrow transplant. After receiving an injection of the radioactive MIBG, your child will need to stay in a special hospital room until the radiation leaves his or her body in the urine. MIBG therapy usually takes a few days.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Neuroblastoma and Learn More about Diseases

Compulsive sexual behavior

Hypoglycemia

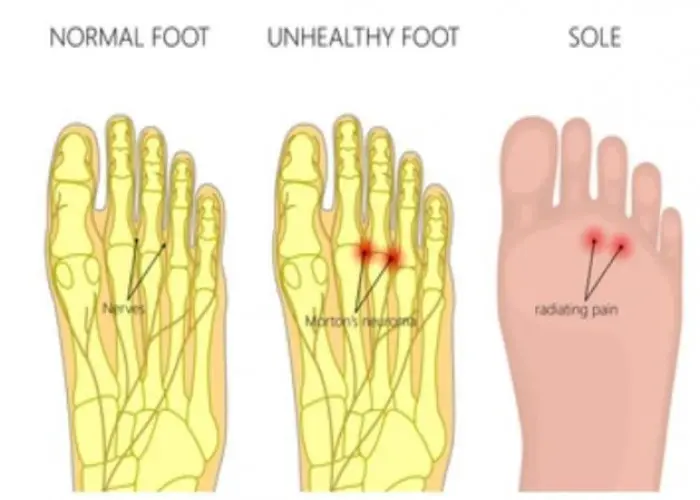

Broken foot

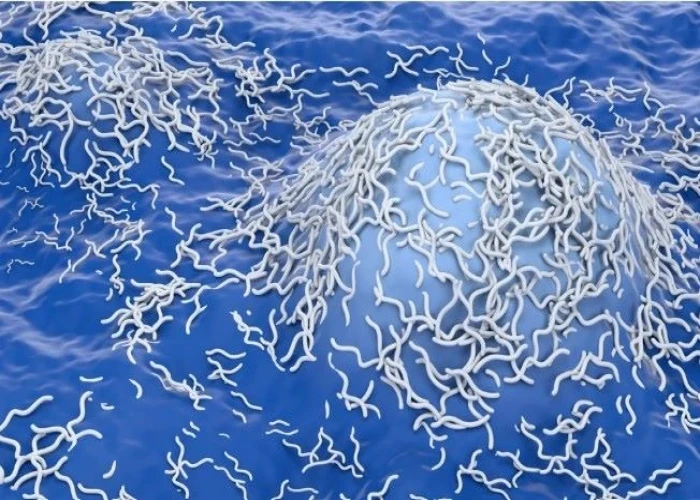

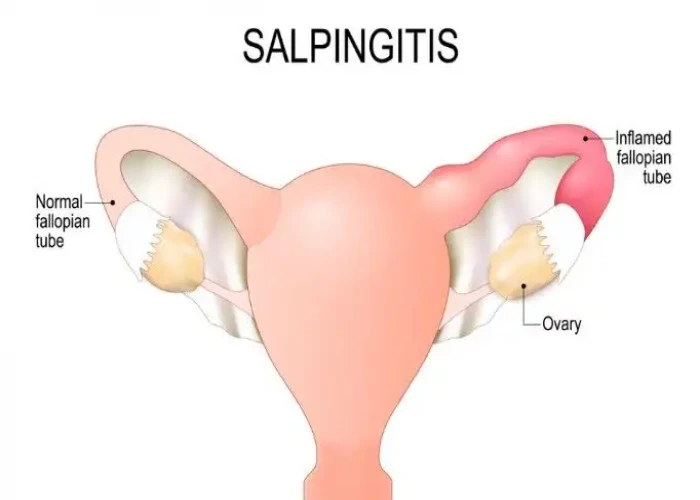

Salpingitis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Dysentery

Benign peripheral nerve tumor

Hepatitis A

neuroblastoma, নিউরোব্লাস্টোমা

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.