Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

Truncus arteriosus

Truncus arteriosus is a congenital heart defect in which the single large blood vessel that normally leaves the heart and branches into the pulmonary artery and aorta fails to separate properly during fetal development. As a result, a single common blood vessel arises from the heart, carrying blood to both the lungs and the body.

In a healthy heart, oxygen-poor blood is pumped from the right ventricle to the lungs through the pulmonary artery, and oxygen-rich blood is pumped from the left ventricle to the body through the aorta. But in truncus arteriosus, oxygen-poor and oxygen-rich blood mix in the common blood vessel, resulting in insufficient oxygen supply to the body and excessive blood flow to the lungs.

Infants with truncus arteriosus usually have symptoms such as difficulty breathing, poor feeding, fatigue, and cyanosis (a blue tinge to the skin). Diagnosis is typically made through imaging tests such as echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Treatment for truncus arteriosus typically involves surgical repair to separate the pulmonary artery from the aorta and create a new pulmonary artery using tissue from the patient's own body or synthetic material. In some cases, a temporary shunt may be placed to increase blood flow to the lungs until the child is stable enough to undergo surgical repair. Long-term follow-up care is necessary to monitor the child's heart function and ensure proper development.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Excessive sleepiness

- Poor growth or weight gain

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Rapid breathing

- Blue skin (cyanosis)

- Loss of consciousness (fainting)

Disease Causes

Truncus arteriosus

Truncus arteriosus occurs when your baby's heart is developing in the womb, and is, therefore, present at birth (congenital). In most cases the cause is unknown.

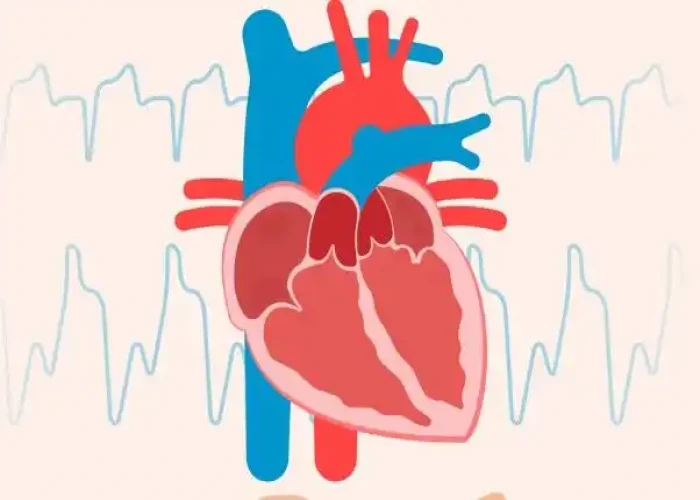

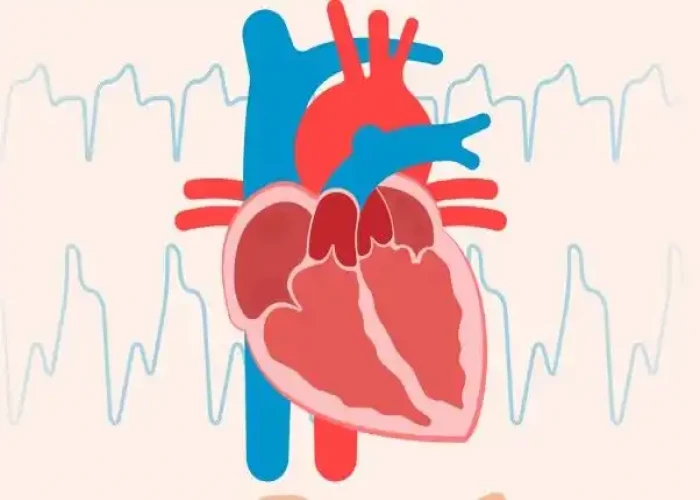

The heart

Your heart has four pumping chambers that circulate your blood. The "doors" of the chambers (valves) control the flow of blood, opening and closing to ensure that blood flows in a single direction.

The heart's four chambers are:

- The right atrium, the upper right chamber, receives oxygen-poor blood from your body and delivers it into the right ventricle.

- The right ventricle, the lower right chamber, pumps the blood through a large vessel called the pulmonary artery and into the lungs, where the blood is resupplied with oxygen.

- The left atrium, the upper left chamber, receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and delivers it into the left ventricle.

- The left ventricle, the lower left chamber, pumps the oxygen-rich blood through a large vessel called the aorta and on to the rest of the body.

Normal heart development

The formation of the fetal heart is complex. At a certain point, all babies have a single large vessel (truncus arteriosus) exiting the heart. During normal development of the heart, however, this very large single vessel divides into two parts.

One part becomes the lower portion of the aorta, which is attached to the left ventricle. The other part becomes the lower portion of the pulmonary artery, which is attached to the right ventricle.

Also during this process, the ventricles develop into two chambers separated by a wall (septum).

Truncus arteriosus in newborns

In babies born with truncus arteriosus, the single large vessel never finished dividing into two separate vessels and the wall separating the two ventricles never closed completely, resulting in a single blood vessel arising from the heart, and a large hole between the two chambers (ventricular septal defect).

In addition to the primary defects of truncus arteriosus, the valve controlling blood flow from the ventricles to the single large vessel (truncal valve) is often defective, so that it does not close completely, allowing blood to flow backward into the heart.

Disease Prevents

Truncus arteriosus

In most cases, congenital heart defects such as truncus arteriosus can't be prevented. If you have a family history of heart defects or if you already have a child with a congenital heart defect, you and your partner might consider talking with a genetic counselor and a cardiologist experienced in congenital heart defects before you make a decision about becoming pregnant.

If you're thinking about becoming pregnant, there are several steps you can take to help ensure a healthy baby, including:

- Getting vaccinated before getting pregnant. Certain viruses, such as German measles (rubella), can be harmful during pregnancy, so it's important to make sure your immunizations are up to date before you get pregnant.

- Avoiding dangerous medications. Check with your doctor before taking any medications if you're pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant. Many drugs aren't recommended for use during pregnancy.

- Taking folic acid. One of the few steps you can take to help prevent birth defects, including spinal cord, brain and possibly heart defects, is to take 400 micrograms of folic acid daily.

- Controlling diabetes. If you're a woman with diabetes, talk to your doctor about pregnancy risks associated with diabetes and how best to manage the disease during your pregnancy.

Disease Treatments

Infants with truncus arteriosus must have surgery. Multiple procedures or surgeries might be necessary, especially as your child grows. Medications might be given before surgery to help improve heart health.

Children and adults with surgically repaired truncus arteriosus must have regular follow-up with their cardiology team.

Medications

Medications that might be prescribed before surgery include:

- Diuretics. Often called water pills, diuretics increase the frequency and volume of urination, preventing fluid from collecting in the body, which is a common effect of heart failure.

- Inotropic agents. This type of medication strengthens the heart's contractions.

Surgical procedures

Most infants with truncus arteriosus have surgery within the first few weeks after birth. The procedure will depend on your baby's condition. Most commonly your baby's surgeon will:

- Close the hole between the two ventricles with a patch

- Separate the upper portion of the pulmonary artery from the single large vessel

- Implant a tube and valve to connect the right ventricle with the upper portion of the pulmonary artery — creating a new, complete pulmonary artery

- Reconstruct the single large vessel and aorta to create a new, complete aorta

After corrective surgery, your child will need lifelong follow-up care with a cardiologist. The cardiologist might recommend that your child limit physical activity, particularly intense competitive sports.

Your child will need to take antibiotics before dental procedures and other surgical procedures to prevent infections.

Because the artificial conduit does not grow with your child, follow-up surgeries to replace the conduit valve are necessary as he or she ages.

Cardiac catheterization

Minimally invasive procedures use a cardiac catheter to avoid the need for traditional heart surgery as your child grows or previously placed artificial valves deteriorate. The catheter is inserted into a blood vessel in the leg that is then threaded up to the heart to replace the conduit.

In addition, cardiac catheterization with an inflatable balloon tip can be used to open up an obstructed or narrowed artery, which might delay the need for follow-up surgery.

Pregnancy

Women who've had surgery to repair truncus arteriosus in infancy need to be evaluated by a cardiologist with expertise in adult congenital heart defects and an obstetrician specializing in high-risk pregnancies before attempting to become pregnant.

Depending on the level of lung damage that occurred before surgery, pregnancy might or might not be recommended. In addition, some drugs taken for heart problems can be harmful to an unborn baby.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Truncus arteriosus and Learn More about Diseases

Head and neck cancers

Small bowel cancer

Bunions

Gastrogenous Diarrhoea

Heart failure

Albinism

Milk allergy

Granuloma annulare

truncus arteriosus, ট্রানকাস আর্টেরিয়াস

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.