Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

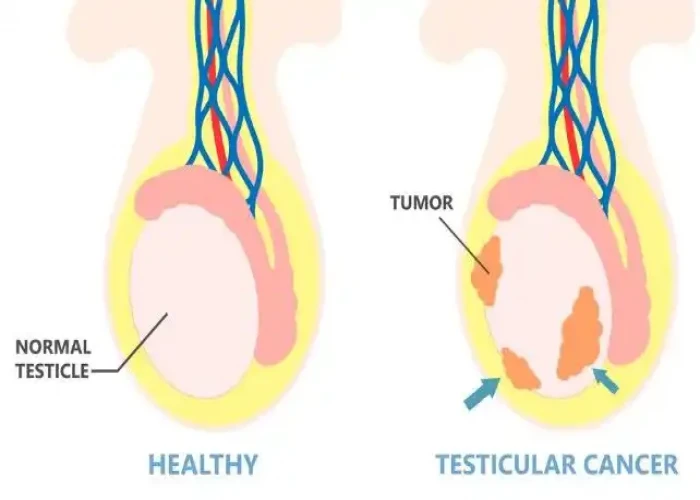

Undescended testicle

An undescended testicle is a medical condition where one or both testicles fail to move from the abdomen, where they form before birth, to the scrotum before or shortly after birth. Normally, testicles descend into the scrotum before birth or in the first few months of life.

Undescended testicles are relatively common in newborns, affecting about 3-5% of full-term male infants. However, in most cases, the testicle will descend on its own within the first year of life. If the testicle does not descend by the age of 1, medical intervention may be necessary.

The cause of undescended testicles is not fully understood, but factors that may contribute include hormonal imbalances, genetic factors, and certain medical conditions.

If left untreated, an undescended testicle can lead to a higher risk of infertility, testicular cancer, and other medical problems. Treatment options may include hormone therapy or surgery to bring the testicle into the scrotum, which can reduce the risk of complications and improve fertility.

It's important to consult a medical professional if you suspect that you or your child may have an undescended testicle, to discuss appropriate treatment options and prevent potential complications.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Testicle pain

- Abdomen pain

- Muscle relaxation

Disease Causes

Undescended testicle

The exact cause of an undescended testicle isn't known. A combination of genetics, maternal health and other environmental factors might disrupt the hormones, physical changes and nerve activity that influence the development of the testicles.

Disease Prevents

Disease Treatments

The goal of treatment is to move the undescended testicle to its proper location in the scrotum. Treatment before 1 year of age might lower the risk of complications of an undescended testicle, such as infertility and testicular cancer. Earlier is better, but it's recommended that surgery takes place before the child is 18 months old.

Surgery

An undescended testicle is usually corrected with surgery. The surgeon carefully manipulates the testicle into the scrotum and stitches it into place (orchiopexy). This procedure can be done either with a laparoscope or with open surgery.

When your son has surgery will depend on a number of factors, such as his health and how difficult the procedure might be. Your surgeon will likely recommend doing the surgery when your son is about 6 months old and before he is 12 months old. Early surgical treatment appears to lower the risk of later complications.

In some cases, the testicle might be poorly developed, abnormal or dead tissue. The surgeon will remove this testicular tissue.

If your son also has an inguinal hernia associated with the undescended testicle, the hernia is repaired during the surgery.

After surgery, the surgeon will monitor the testicle to see that it continues to develop, function properly and stay in place. Monitoring might include:

- Physical exams

- Ultrasound exams of the scrotum

- Tests of hormone levels

Hormone treatment

Hormone treatment involves the injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). This hormone could cause the testicle to move to your son's scrotum. Hormone treatment is not usually recommended because it is much less effective than surgery.

Other treatments

If your son doesn't have one or both testicles — because one or both are missing or didn't survive after surgery — you might consider saline testicular prostheses for the scrotum that can be implanted during late childhood or adolescence. These prostheses give the scrotum a normal appearance.

If your son doesn't have at least one healthy testicle, your child's doctor will refer him to a hormone specialist (endocrinologist) to discuss future hormone treatments that would be necessary to bring about puberty and physical maturity.

Results

Orchiopexy, the most common surgical procedure for correcting a single descending testicle, has a success rate of nearly 100 percent. Fertility for males after surgery with a single undescended testicle is nearly normal, but falls to 65 percent in men with two undescended testicles. Surgery might reduce the risk of testicular cancer, but does not eliminate it.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Undescended testicle and Learn More about Diseases

Febrile seizure

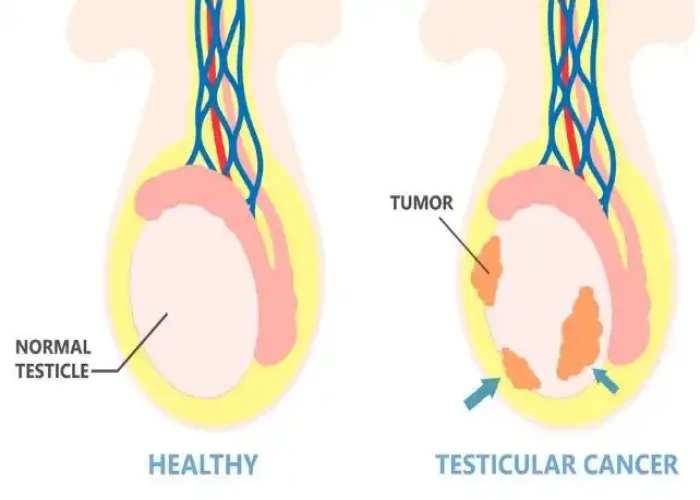

Thoracic aortic aneurysm

Fuchs' dystrophy

Occupational asthma

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Pink eye (conjunctivitis)

COPD

Stomach polyps

undescended testicle, অনাকাঙ্ক্ষিত অন্ডকোষ

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.