Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

Metachromatic leukodystrophy

Metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) is a rare genetic disorder that affects the nervous system. It is caused by a deficiency of an enzyme called arylsulfatase A, which leads to the buildup of a fatty substance called sulfatide in the brain and nervous system.

MLD is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that a person must inherit two copies of the mutated gene (one from each parent) to develop the condition. Symptoms of MLD typically appear in early childhood or adolescence, and can include muscle weakness, stiffness, tremors, seizures, vision loss, and cognitive decline.

There is currently no cure for MLD, but treatment options can help manage symptoms and slow the progression of the disease. These may include bone marrow transplantation, enzyme replacement therapy, and symptomatic treatments such as physical and occupational therapy, medications, and supportive care.

Due to its rare and complex nature, MLD is typically managed by a team of healthcare professionals, including neurologists, geneticists, and other specialists who can provide comprehensive care and support for affected individuals and their families.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Memory loss

- Muscle weakness

- Weak muscle tone (hypotonia)

- Decreased hearing

- Seizures

- Loss of motor skills, such as walking, moving, speaking and swallowing

- Stiff, rigid muscles, poor muscle function and paralysis

- Emotional and behavioral problems, including unstable emotions and substance misuse

Disease Causes

Metachromatic leukodystrophy

Metachromatic leukodystrophy is an inherited disorder caused by an abnormal (mutated) gene. The condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. The abnormal recessive gene is located on one of the nonsex chromosomes (autosomes). To inherit an autosomal recessive disorder, both parents must be carriers, but they do not typically show signs of the condition. The affected child inherits two copies of the abnormal gene — one from each parent.

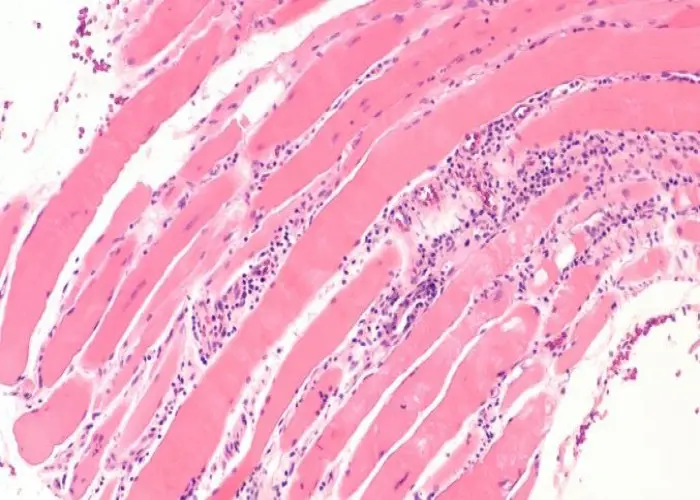

The most common cause of metachromatic leukodystrophy is a mutation in the ARSA gene. This mutation results in a lack of the enzyme that breaks down lipids called sulfatides that build up in the myelin.

Rarely, metachromatic leukodystrophy is caused by a deficiency in another kind of protein (activator protein) that breaks down sulfatides. This is caused by a mutation in the PSAP gene.

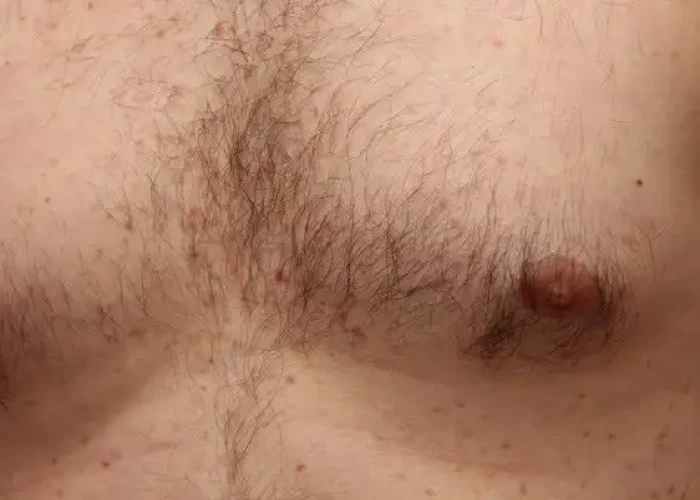

The buildup of sulfatides is toxic, destroying the myelin-producing cells ― also called white matter ― that protect the nerves. This results in damage to the function of nerve cells in the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves.

Disease Prevents

Disease Treatments

Metachromatic leukodystrophy can't be cured yet, but clinical trials hold some promise for future treatment. Current treatment is aimed at preventing nerve damage, slowing progression of the disorder, preventing complications and providing supportive care. Early recognition and intervention may improve outcomes for some people with the disorder.

As the disorder progresses, the level of care required to meet daily needs increases. Your health care team will work with you to help manage signs and symptoms and try to improve quality of life. Talk to your doctor about the possibility of participating in a clinical trial.

Metachromatic leukodystrophy can be managed with several treatment approaches:

- Medications. Medications may reduce signs and symptoms, such as behavioral problems, seizures, difficulty with sleeping, gastrointestinal issues, infection and pain.

- Physical, occupational and speech therapy. Physical therapy to promote muscle and joint flexibility and maintain range of motion may be helpful. Occupational and speech therapy can help maintain functioning.

- Nutritional assistance. Working with a nutrition specialist (dietitian) can help provide proper nutrition. Eventually, it may become difficult to swallow food or liquid. This may require assistive feeding devices as the condition progresses.

- Other treatments. Other treatments may be needed as the condition progresses. Examples include a wheelchair, walker or other assistive devices; mechanical ventilation to assist with breathing; treatments to prevent or address complications; and long-term care or hospitalization.

Care for metachromatic leukodystrophy can be complex and change over time. Regular follow-up appointments with a team of medical professionals experienced in managing this disorder may help prevent certain complications and link you with appropriate support at home, school or work.

Potential future treatments

Potential treatments for metachromatic leukodystrophy that are being studied include:

- Gene therapy and other types of cell therapy that introduce healthy genes to replace diseased ones

- Enzyme replacement or enhancement therapy to decrease buildup of fatty substances

- Substrate reduction therapy, which reduces the production of fatty substances

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Metachromatic leukodystrophy and Learn More about Diseases

Traveler's diarrhea

Posterior cortical atrophy

Systemic mastocytosis

Bedsores (pressure ulcers)

Broken leg

Dermatomyositis

Schizoid personality disorder

Prostatitis

metachromatic leukodystrophy, mld, মেটাক্রোমেটিক লিউকোডিস্ট্রোফি, এমএলডি

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.