Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

Mitral valve prolapse

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a condition that occurs when the valve between the left atrium and left ventricle of the heart, called the mitral valve, does not close properly. In people with MVP, the valve flaps may be too large or floppy, causing them to bulge back into the left atrium when the heart contracts.

MVP is a relatively common condition that affects up to 10% of the population, but most people with MVP have no symptoms and do not require treatment. However, in some cases, MVP can cause symptoms such as palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, and fatigue. Rarely, MVP can lead to more serious complications, such as mitral regurgitation or infective endocarditis.

The exact cause of MVP is not fully understood, but it is believed to be related to a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Risk factors for MVP may include a family history of the condition, connective tissue disorders, and certain medical conditions such as Marfan syndrome.

Diagnosis of MVP typically involves a physical exam and tests such as an echocardiogram, which uses sound waves to create images of the heart. Treatment for MVP may depend on the presence and severity of symptoms. In most cases, lifestyle changes such as regular exercise, stress reduction, and avoiding stimulants such as caffeine can help manage symptoms. Medications such as beta blockers or calcium channel blockers may also be prescribed to manage symptoms or prevent complications.

In rare cases where MVP is causing severe symptoms or complications, surgery or other procedures may be necessary to repair or replace the mitral valve. However, for most people with MVP, regular monitoring and management of symptoms is all that is required to maintain heart health and prevent complications.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmia)

- Dizziness (vertigo)

- Dizziness, lightheadedness or faintness

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Fatigue (Tiredness)

Disease Causes

Mitral valve prolapse

To understand the causes of mitral valve disease, it may be helpful to know how the heart works.

The mitral valve is one of four valves in the heart that keep blood flowing in the right direction. Each valve has flaps (leaflets) that open and close once during each heartbeat. If a valve doesn't open or close properly, blood flow through the heart to the body can be reduced.

In mitral valve prolapse, one or both of the mitral valve leaflets have extra tissue or stretch more than usual. The leaflets can bulge backward (prolapse) like a parachute into the left upper heart chamber (left atrium) each time the heart contracts to pump blood.

The bulging may keep the valve from closing tightly. If blood leaks backward through the valve, the condition is called mitral valve regurgitation.

Disease Prevents

Disease Treatments

Most people with mitral valve prolapse, particularly people without symptoms, don't require treatment.

If you have mitral valve regurgitation but don't have symptoms, your health care provider may recommend regular checkups to monitor your condition.

If you have severe mitral valve regurgitation, medications or surgery may be needed even if you don't have symptoms.

Medications

Medications may be needed to treat irregular heartbeats or other complications of mitral valve prolapse. Medications include:

- Beta blockers. These drugs relax blood vessels and slow the heartbeat, which reduces blood pressure.

- Water pills (diuretics). These medicines help remove salt (sodium) and water through your urine, reducing blood pressure.

- Heart rhythm drugs (antiarrhythmics). Medications may be used to help control irregular heart rhythms.

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants). If mitral valve disease is causing an irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation, your health care provider may recommend blood-thinning drugs to prevent blood clots. Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of blood clots and strokes. If you had mitral valve replacement with a mechanical valve, blood thinners are needed for life.

- Antibiotics. The American Heart Association says antibiotics aren't usually necessary for someone with mitral valve prolapse. But if you've had mitral valve replacement, your care provider may recommend taking antibiotics before dental procedures to prevent a heart infection called infective endocarditis.

Surgery and other procedures

Most people with mitral valve prolapse don't need surgery. But surgery may be recommended if mitral prolapse causes severe mitral valve regurgitation, whether or not you have symptoms.

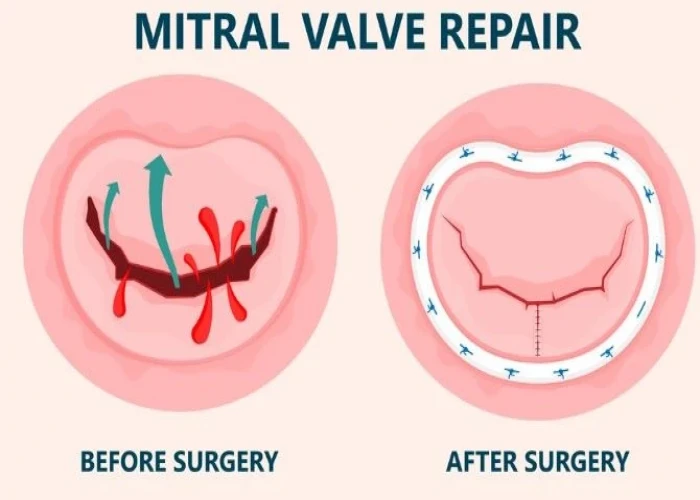

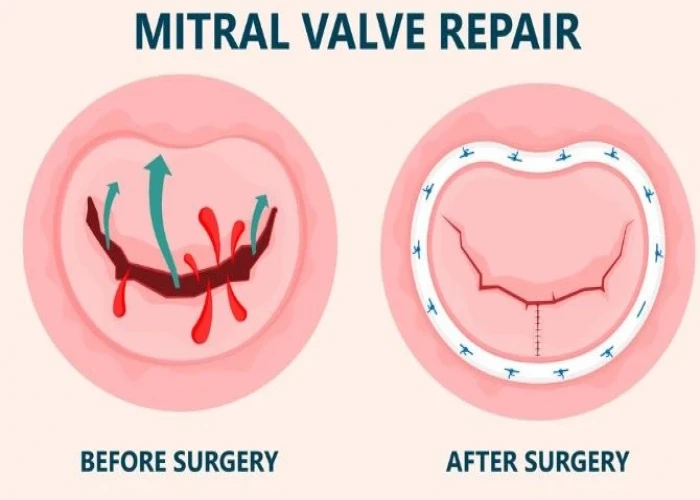

Surgery for a diseased or damaged mitral valve includes mitral valve repair or mitral valve replacement. Mitral valve repair is preferred because it saves the existing valve.

Valve repair and replacement may be done using open-heart surgery or minimally invasive surgery. Minimally invasive surgery involves smaller incisions and may have less blood loss and a quicker recovery time.

During mitral valve repair surgery, the surgeon might remove excess tissue from the prolapsed valve so the flaps can close tightly. The surgeon may also replace the cords that support the valve. Other repairs may also be done.

If mitral valve repair isn't possible, the valve may be replaced. During mitral valve replacement surgery, a surgeon removes the mitral valve and replaces it with a mechanical valve or a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue (biological tissue valve).

Sometimes, a heart catheter procedure is done to place a replacement valve into a biological tissue valve that no longer works well. This is called a valve-in-valve procedure.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Mitral valve prolapse and Learn More about Diseases

MCAD deficiency

Wilson's disease

Spinal headaches

Glomerulonephritis

Diphtheria

E. coli

Yeast infection (vaginal)

Tendinitis

mitral valve prolapse, মিত্রাল ভালভ প্রল্যাপস

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.