Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes, also known as insulin-dependent diabetes or juvenile-onset diabetes, is a chronic condition in which the body's immune system attacks and destroys the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Insulin is a hormone that regulates the amount of glucose in the blood, and without enough insulin, glucose builds up in the bloodstream instead of being used for energy.

As a result, people with type 1 diabetes need to take insulin injections or use an insulin pump to manage their blood glucose levels. They also need to monitor their blood glucose regularly and make adjustments to their insulin dosage, food intake, and physical activity to avoid hyperglycemia (high blood glucose) or hypoglycemia (low blood glucose).

Type 1 diabetes typically develops in childhood or adolescence, although it can occur at any age. The exact cause of type 1 diabetes is not fully understood, but it is believed to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There is currently no cure for type 1 diabetes, but with proper management, people with the condition can live long and healthy lives.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Excessive thirst

- Bed-wetting in children who previously didn't wet the bed during the night

- Blurred vision of eye

- Weakness

- Fatigue (Tiredness)

- Rapid mood chang

- Weight loss

- Extreme hunger

- Frequent urination at night (nocturia)

- Frequent urination

- Diabetes

Disease Causes

Type 1 diabetes

The exact cause of type 1 diabetes is unknown. Usually, the body's own immune system — which normally fights harmful bacteria and viruses — mistakenly destroys the insulin-producing (islet, or islets of Langerhans) cells in the pancreas. Other possible causes include:

- Genetics

- Exposure to viruses and other environmental factors

The role of insulin

Once a significant number of islet cells are destroyed, you'll produce little or no insulin. Insulin is a hormone that comes from a gland situated behind and below the stomach (pancreas).

- The pancreas secretes insulin into the bloodstream.

- Insulin circulates, allowing sugar to enter your cells.

- Insulin lowers the amount of sugar in your bloodstream.

- As your blood sugar level drops, so does the secretion of insulin from your pancreas.

The role of glucose

Glucose — a sugar — is a main source of energy for the cells that make up muscles and other tissues.

- Glucose comes from two major sources: food and your liver.

- Sugar is absorbed into the bloodstream, where it enters cells with the help of insulin.

- Your liver stores glucose as glycogen.

- When your glucose levels are low, such as when you haven't eaten in a while, the liver breaks down the stored glycogen into glucose to keep your glucose levels within a normal range.

In type 1 diabetes, there's no insulin to let glucose into the cells, so sugar builds up in your bloodstream. This can cause life-threatening complications.

Disease Prevents

Type 1 diabetes

There's no known way to prevent type 1 diabetes. But researchers are working on preventing the disease or further destruction of the islet cells in people who are newly diagnosed.

Ask your doctor if you might be eligible for one of these clinical trials, but carefully weigh the risks and benefits of any treatment available in a trial.

Disease Treatments

Treatment for type 1 diabetes includes:

- Taking insulin

- Carbohydrate, fat and protein counting

- Frequent blood sugar monitoring

- Eating healthy foods

- Exercising regularly and maintaining a healthy weight

The goal is to keep your blood sugar level as close to normal as possible to delay or prevent complications. Generally, the goal is to keep your daytime blood sugar levels before meals between 80 and 130 mg/dL (4.44 to 7.2 mmol/L) and your after-meal numbers no higher than 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L) two hours after eating.

Insulin and other medications

Anyone who has type 1 diabetes needs lifelong insulin therapy.

Types of insulin are many and include:

- Short-acting (regular) insulin

- Rapid-acting insulin

- Intermediate-acting (NPH) insulin

- Long-acting insulin

Examples of short-acting (regular) insulin include Humulin R and Novolin R. Rapid-acting insulin examples are insulin glulisine (Apidra), insulin lispro (Humalog) and insulin aspart (Novolog). Long-acting insulins include insulin glargine (Lantus, Toujeo Solostar), insulin detemir (Levemir) and insulin degludec (Tresiba). Intermediate-acting insulins include insulin NPH (Novolin N, Humulin N).

Insulin administration

Insulin can't be taken orally to lower blood sugar because stomach enzymes will break down the insulin, preventing its action. You'll need to receive it either through injections or an insulin pump.

- Injections. You can use a fine needle and syringe or an insulin pen to inject insulin under your skin. Insulin pens look similar to ink pens and are available in disposable or refillable varieties.

- If you choose injections, you'll likely need a mixture of insulin types to use throughout the day and night. Multiple daily injections that include a combination of a long-acting insulin combined with a rapid-acting insulin more closely mimic the body's normal use of insulin than do older insulin regimens that only required one or two shots a day. A regimen of three or more insulin injections a day has been shown to improve blood sugar levels.

- An insulin pump. You wear this device, which is about the size of a cellphone, on the outside of your body. A tube connects a reservoir of insulin to a catheter that's inserted under the skin of your abdomen. This type of pump can be worn in a variety of ways, such as on your waistband, in your pocket or with specially designed pump belts.

- There's also a wireless pump option. You wear a pod that houses the insulin reservoir on your body that has a tiny catheter that's inserted under your skin. The insulin pod can be worn on your abdomen, lower back, or on a leg or an arm. The programming is done with a wireless device that communicates with the pod.

- Pumps are programmed to dispense specific amounts of rapid-acting insulin automatically. This steady dose of insulin is known as your basal rate, and it replaces whatever long-acting insulin you were using.

- When you eat, you program the pump with the amount of carbohydrates you're eating and your current blood sugar, and it will give you what's called a bolus dose of insulin to cover your meal and to correct your blood sugar if it's elevated. Some research has found that in some people an insulin pump can be more effective at controlling blood sugar levels than injections. But many people achieve good blood sugar levels with injections, too. An insulin pump combined with a continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) device may provide even tighter blood sugar control.

Artificial pancreas

In September 2016, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first artificial pancreas for people with type 1 diabetes who are age 14 and older. A second artificial pancreas was approved in December 2019.

It's also called closed-loop insulin delivery. The implanted device links a continuous glucose monitor, which checks blood sugar levels every five minutes, to an insulin pump. The device automatically delivers the correct amount of insulin when the monitor indicates it's needed.

There are more artificial pancreas (closed loop) systems currently in clinical trials.

Other medications

Additional medications also may be prescribed for people with type 1 diabetes, such as:

- High blood pressure medications. Your doctor may prescribe angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) to help keep your kidneys healthy. These medications are recommended for people with diabetes who have blood pressures above 140/90 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg).

- Aspirin. Your doctor may recommend you take baby or regular aspirin daily to protect your heart if your doctor feels you have an increased risk for a cardiovascular event, after discussing with you the potential risk of bleeding.

- Cholesterol-lowering drugs. Cholesterol guidelines tend to be more aggressive for people with diabetes because of the elevated risk of heart disease. The American Diabetes Association recommends that low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or "bad") cholesterol be below 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L). Your high-density lipoprotein (HDL, or "good") cholesterol is recommended to be over 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) in women and over 40 mg/dL (1 mmol/L) in men. Triglycerides, another type of blood fat, are ideal when they're less than 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L).

Blood sugar monitoring

Depending on what type of insulin therapy you select or require, you may need to check and record your blood sugar level at least four times a day.

The American Diabetes Association recommends testing blood sugar levels before meals and snacks, before bed, before exercising or driving, and if you suspect you have low blood sugar. Careful monitoring is the only way to make sure that your blood sugar level remains within your target range — and more frequent monitoring can lower A1C levels.

Even if you take insulin and eat on a rigid schedule, blood sugar levels can change unpredictably. You'll learn how your blood sugar level changes in response to food, activity, illness, medications, stress, hormonal changes and alcohol.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is the newest way to monitor blood sugar levels, and may be especially helpful for preventing hypoglycemia. The devices have been shown to lower A1C.

Continuous glucose monitors attach to the body using a fine needle just under the skin that checks blood glucose level every few minutes. CGM isn't yet considered as accurate as standard blood sugar monitoring, so at this time it's still important to check your blood sugar levels manually.

Healthy eating and monitoring carbohydrates

There's no such thing as a diabetes diet. However, it's important to center your diet on nutritious, low-fat, high-fiber foods such as:

- Fruits

- Vegetables

- Whole grains

Your dietitian will recommend that you eat fewer animal products and refined carbohydrates, such as white bread and sweets. This healthy-eating plan is recommended even for people without diabetes.

You'll need to learn how to count the amount of carbohydrates in the foods you eat so that you can give yourself enough insulin to properly metabolize those carbohydrates. A registered dietitian can help you create a meal plan that fits your needs.

Physical activity

Everyone needs regular aerobic exercise, and people who have type 1 diabetes are no exception. First, get your doctor's OK to exercise. Then choose activities you enjoy, such as walking or swimming, and make them part of your daily routine. Aim for at least 150 minutes of aerobic exercise a week, with no more than two days without any exercise. The goal for children is at least an hour of activity a day.

Remember that physical activity lowers blood sugar. If you begin a new activity, check your blood sugar level more often than usual until you know how that activity affects your blood sugar levels. You might need to adjust your meal plan or insulin doses to compensate for the increased activity.

Situational concerns

Certain life circumstances call for different considerations.

- Driving. Hypoglycemia can occur at any time. It's a good idea to check your blood sugar anytime you're getting behind the wheel. If it's below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), have a snack with 15 grams of carbohydrates. Retest again in 15 minutes to make sure it has risen to a safe level.

- Working. Type 1 diabetes can pose some challenges in the workplace. For example, if you work in a job that involves driving or operating heavy machinery, hypoglycemia could pose a serious risk to you and those around you. You may need to work with your doctor and your employer to ensure that certain accommodations are made, such as additional breaks for blood sugar testing and fast access to food and drink. There are federal and state laws in place that require employers to make reasonable accommodations for people with diabetes.

- Being pregnant. Because the risk of pregnancy complications is higher for women with type 1 diabetes, experts recommend that women have a preconception evaluation and that A1C readings ideally should be less than 6.5% before they attempt to get pregnant.

- The risk of birth defects is increased for women with type 1 diabetes, particularly when diabetes is poorly controlled during the first six to eight weeks of pregnancy. Careful management of your diabetes during pregnancy can decrease your risk of complications.

- Being older. For those who are frail or sick or have cognitive deficits, tight control of blood sugar may not be practical and could increase the risk of hypoglycemia. For many people with type 1 diabetes, a less stringent A1C goal of less than 8% may be appropriate.

Potential future treatments

- Pancreas transplant. With a successful pancreas transplant, you would no longer need insulin. But pancreas transplants aren't always successful — and the procedure poses serious risks. Because these risks can be more dangerous than the diabetes itself, pancreas transplants are generally reserved for those with very difficult-to-manage diabetes, or for people who also need a kidney transplant.

- Islet cell transplantation. Researchers are experimenting with islet cell transplantation, which provides new insulin-producing cells from a donor pancreas. Although this experimental procedure had some problems in the past, new techniques and better drugs to prevent islet cell rejection may improve its future chances of becoming a successful treatment.

Signs of trouble

Despite your best efforts, sometimes problems will arise. Certain short-term complications of type 1 diabetes, such as hypoglycemia, require immediate care.

Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). This occurs when your blood sugar level drops below your target range. Ask your doctor what's considered a low blood sugar level for you. Blood sugar levels can drop for many reasons, including skipping a meal, eating fewer carbohydrates than called for in your meal plan, getting more physical activity than normal or injecting too much insulin.

Learn the symptoms of hypoglycemia, and test your blood sugar if you think your levels are dropping. When in doubt, always test your blood sugar. Early signs and symptoms of low blood sugar include:

- Sweating

- Shakiness

- Hunger

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Rapid or irregular heart rate

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Blurred vision

- Irritability

Later signs and symptoms of low blood sugar, which can sometimes be mistaken for alcohol intoxication in teens and adults, include:

- Lethargy

- Confusion

- Behavior changes, sometimes dramatic

- Poor coordination

- Convulsions

Nighttime hypoglycemia may cause you to wake with sweat-soaked pajamas or a headache. Due to a natural rebound effect, nighttime hypoglycemia sometimes might cause an unusually high blood sugar reading first thing in the morning, also known as Somogyi effect.

If you have a low blood sugar reading:

- Have 15 to 20 grams of a fast-acting carbohydrate, such as fruit juice, glucose tablets, hard candy, regular (not diet) soda or another source of sugar. Avoid foods with added fat, which don't raise blood sugar as quickly because fat slows sugar absorption.

- Retest your blood sugar in about 15 minutes to make sure it's normal.

- If it's still low, have another 15 to 20 grams of carbohydrate and retest in another 15 minutes.

- Repeat until you get a normal reading.

- Eat a mixed food source, such as peanut butter and crackers, to help stabilize your blood sugar.

If a blood glucose meter isn't readily available, treat for low blood sugar anyway if you have symptoms of hypoglycemia, and then test as soon as possible.

Left untreated, low blood sugar will cause you to lose consciousness. If this occurs, you may need an emergency injection of glucagon — a hormone that stimulates the release of sugar into the blood. Be sure you always have an unexpired glucagon emergency kit available at home, at work and when you're out. Make sure that co-workers, family and friends know how to use the kit in case you are unable to give yourself the injection.

Hypoglycemia unawareness. Some people may lose the ability to sense that their blood sugar levels are getting low, called hypoglycemia unawareness. The body no longer reacts to a low blood sugar level with symptoms such as lightheadedness or headaches. The more you experience low blood sugar, the more likely you are to develop hypoglycemia unawareness. If you can avoid having a hypoglycemic episode for several weeks, you may start to become more aware of impending lows. Sometimes increasing the blood sugar target (for example, from 80 to 120 mg/DL to 100 to 140 mg/DL) at least temporarily can also help improve hypoglycemia awareness.

High blood sugar (hyperglycemia). Your blood sugar can rise for many reasons, including eating too much, eating the wrong types of foods, not taking enough insulin or fighting an illness.

Watch for:

- Frequent urination

- Increased thirst

- Blurred vision

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Hunger

- Difficulty concentrating

If you suspect hyperglycemia, check your blood sugar. If your blood sugar is higher than your target range, you'll likely need to administer a "correction" — an additional dose of insulin that should bring your blood sugar back to normal. High blood sugar levels don't come down as quickly as they go up. Ask your doctor how long to wait until you recheck. If you use an insulin pump, random high blood sugar readings may mean you need to change the pump site.

If you have a blood sugar reading above 240 mg/dL (13.3 mmol/L), test for ketones using a urine test stick. Don't exercise if your blood sugar level is above 240 mg/dL or if ketones are present. If only a trace or small amounts of ketones are present, drink extra fluids to flush out the ketones.

If your blood sugar is persistently above 300 mg/dL (16.7 mmol/L), or if your urine ketones remain high despite taking appropriate correction doses of insulin, call your doctor or seek emergency care.

Increased ketones in your urine (diabetic ketoacidosis). If your cells are starved for energy, your body may begin to break down fat — producing toxic acids known as ketones. Diabetic ketoacidosis is a life-threatening emergency.

Signs and symptoms of this serious condition include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- A sweet, fruity smell on your breath

- Weight loss

If you suspect ketoacidosis, check your urine for excess ketones with an over-the-counter ketones test kit. If you have large amounts of ketones in your urine, call your doctor right away or seek emergency care. Also, call your doctor if you have vomited more than once and you have ketones in your urine.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

-

Ammonium aceticum

6, 30 strength.

-

Acid aceticum

6, 30 strength.

-

Codeinum

30, 200 strength.

-

Terebinthina

30 strength.

-

Insulin

3X strength.

-

Cantharis

6, 30, 200 power.

-

Helonias

Q power.

-

Lactic acid

3, 6, 30 power.

-

Arsenicum bromatum

Q power.

-

Kreosotum

6, 30 strength.

-

Syzygium jambolanum

1X strength.

-

Acidum phosphoricum

30 strength.

-

Uranium nitricum

3X strength.

-

Argentum metallicum

3X strength.

Disease yoga

Type 1 diabetes and Learn More about Diseases

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Phenylketonuria (PKU)

Uveitis

Lung cancer

Hepatitis C

Common cold

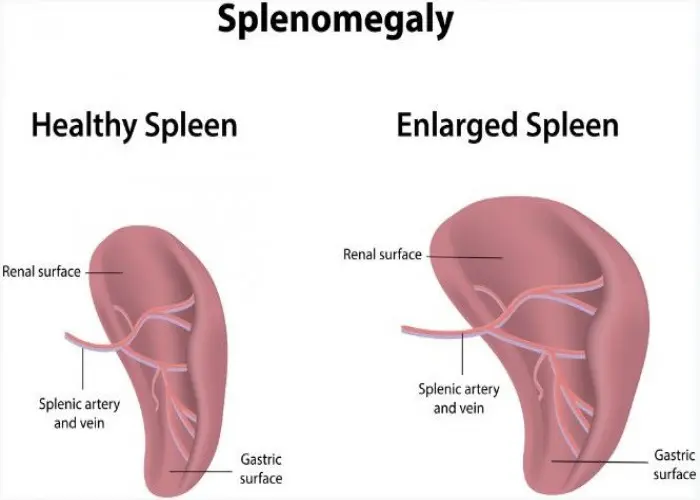

Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly)

Diabetic hypoglycemia

type 1 diabetes, টাইপ ১ ডায়াবেটিস

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.