Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

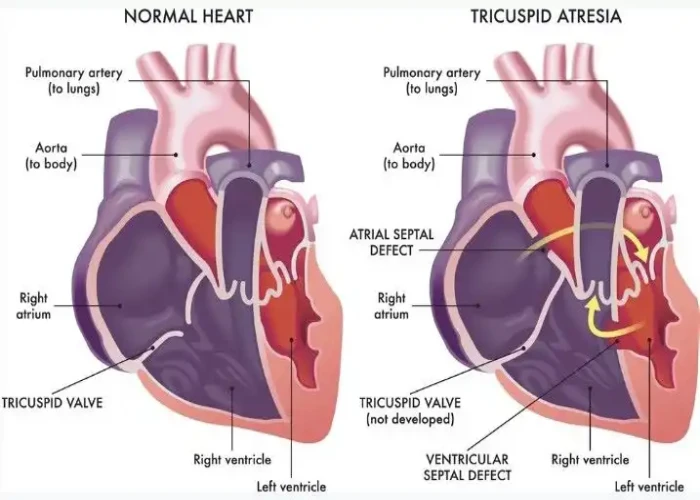

Tricuspid atresia

Tricuspid atresia is a congenital heart defect in which the tricuspid valve, which normally controls blood flow between the right atrium and right ventricle of the heart, fails to develop properly. This can cause the right ventricle to be underdeveloped and unable to pump blood effectively to the lungs.

The severity of tricuspid atresia can vary depending on the degree of underdevelopment of the right ventricle and the presence of other related heart defects. Symptoms of tricuspid atresia may include blue-tinged skin, difficulty breathing, fatigue, poor feeding, and slow growth. Babies with this condition may also be at risk of developing blood clots in the veins that carry blood to the lungs.

Diagnosis of tricuspid atresia is typically made through imaging tests such as echocardiography and cardiac catheterization. Treatment for tricuspid atresia may involve a series of surgeries to reroute blood flow in the heart, including the creation of a connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta (known as a Fontan procedure) and the placement of a prosthetic valve to regulate blood flow. Medications such as diuretics or blood thinners may also be used to manage symptoms and reduce the risk of complications.

Long-term outlook for people with tricuspid atresia can vary depending on the severity of the condition and the effectiveness of treatment. With appropriate medical care and close monitoring, many people with this condition are able to lead active, healthy lives.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Blue skin (cyanosis)

- Swollen abdomen (Ascites)

- Swollen (Edema)

- Swelling (edema) in your hands and feet

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Weakness

- Fatigue (Tiredness)

- Poor growth or weight gain

- Difficulty breathing (dyspnea)

- Blue lips (cyanosis)

- Rapid weight gain

Disease Causes

Tricuspid atresia

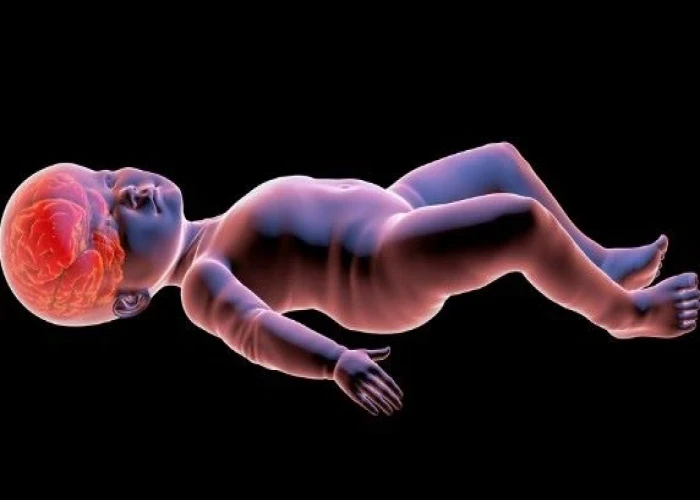

Tricuspid atresia occurs during fetal heart development. Some genetic factors, such as Down syndrome, might increase your baby's risk of congenital heart defects such as tricuspid atresia, but the cause of congenital heart disease is usually unknown.

How the heart works

Your heart is divided into four chambers — the right atrium and right ventricle and left atrium and left ventricle. The right side of the heart moves blood to the lungs, where it picks up oxygen before it circulates to your heart's left side. The left side pumps blood into a large vessel called the aorta, which circulates the oxygen-rich blood to the rest of your body.

Valves control the flow of blood into and out of your heart. These valves open to allow blood to move to the next chamber or one of the arteries, and they close to keep blood from flowing backward.

When things go wrong

In tricuspid atresia, the right side of the heart can't pump enough blood to the lungs because the tricuspid valve is missing. A sheet of tissue blocks the flow of blood from the right atrium to the right ventricle. As a result, the right ventricle is usually small and underdeveloped (hypoplastic).

Blood instead flows from the right atrium to the left atrium through a hole in the wall between them (septum). This hole is either a heart defect (atrial septal defect) or an enlarged natural opening that's supposed to close soon after birth (patent foramen ovale).

After the blood flows to the left atrium, it enters the left ventricle and then is pumped to the aorta. To get to the lungs, blood flows through a vessel that connects the aorta to the pulmonary artery (ductus arteriosus). All hearts have a ductus arteriosus while the baby is in the uterus, but shortly after birth, the ductus closes.

A baby with tricuspid atresia might need medication to keep the ductus from closing after birth. A procedure or surgery to create an opening between the atria or to provide a connection from the aorta to the pulmonary artery might be needed.

Many babies born with tricuspid atresia have a hole between the ventricles (ventricular septal defect). In these cases, some blood can flow through the hole between the left ventricle and the right ventricle, and then blood is pumped to the lungs through the pulmonary artery.

However, the valve between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery (pulmonary valve) might be narrowed, which can reduce blood flow to the lungs. If the pulmonary valve isn't narrowed and if the ventricular septal defect is large, too much blood can flow to the lungs, which can lead to heart failure.

Some babies have other heart defects as well.

Disease Prevents

Tricuspid atresia

Congenital heart defects such as tricuspid atresia usually aren't preventable. If you have a family history of heart defects or a child with a congenital heart defect, a genetic counselor and a cardiologist experienced in congenital heart defects can help you look at risks associated with future pregnancies.

Some steps you can take that might reduce your baby's risk of heart and other birth defects in pregnancy include:

- Get adequate folic acid. Take 400 micrograms of folic acid daily. This amount, which is often in prenatal vitamins, has been shown to reduce brain and spinal cord defects, and folic acid may help prevent heart defects, too.

- Talk with your doctor about medication use. Whether you're taking prescription or over-the-counter drugs, an herbal product or a dietary supplement, check with your doctor before using them during pregnancy.

- Avoid smoking or drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Either can increase the risk of congenital heart defects.

- Avoid chemical exposure, whenever possible. While you're pregnant, it's best to stay away from chemicals, including cleaning products and paint, as much as you can.

Disease Treatments

There's no way to replace a tricuspid valve in tricuspid atresia. Treatment involves surgery to ensure enough blood flow through the heart and into the lungs.

Often, this requires more than one surgery. Medications to strengthen the heart muscle, lower blood pressure and rid the baby's body of excess fluid and supplemental oxygen to help the baby breathe also might be given before surgery.

Medications

Before surgery, your child's cardiologist might recommend that your child take the hormone prostaglandin to help widen (dilate) and keep open the ductus arteriosus.

Surgeries or other procedures

Some of the procedures used to treat tricuspid atresia are a temporary fix to increase blood flow (palliative surgeries). Procedures that might be needed include:

- Atrial septostomy. Rarely, a balloon is used to create or enlarge the opening between the heart's upper chambers to allow more blood to flow from the right atrium to the left atrium.

- Shunting. This creates a bypass (shunt) from a main blood vessel leading out of the heart to the blood vessel leading to the lungs (pulmonary artery), which improves oxygen levels.

- Surgeons generally implant a shunt during the first two weeks of life. However, babies usually outgrow this shunt and might need another surgery to replace it.

- Pulmonary artery band placement. If your baby has a ventricular septal defect and too much blood flowing to the lungs from the heart, a surgeon might place a band around the pulmonary artery to reduce the flow.

- Glenn operation. When babies outgrow the first shunt, they often require this surgery, which sets the stage for the more permanent corrective surgery, called the Fontan procedure.

- Doctors usually perform the Glenn operation when a child is between 3 and 6 months old. Doctors remove the first shunt, then connect one of the large veins that normally returns blood to the heart (the superior vena cava) to the pulmonary artery instead.

- This procedure allows blood to flow directly to the lungs and reduces the workload on the left ventricle, decreasing the risk of damage to it.

- Fontan procedure. A variation of this standard treatment of tricuspid atresia is usually done when the child is 2 to 5 years old. In general, the surgeon creates a path for the blood that's returning to the heart (the inferior vena cava) to flow directly into the pulmonary arteries, which then transport the blood into the lungs.

- Doctors sometimes leave an opening between the pathway and the right atrium (fenestration).

Follow-up care

To monitor heart health, you or your child will need lifelong follow-up care with a cardiologist who specializes in congenital heart disease.

Your or your child's cardiologist will tell you whether you or your child needs to take preventive antibiotics before dental and other procedures. In some cases, your child's cardiologist might recommend limiting vigorous physical activity.

The short- and intermediate-term outlook for children who have a Fontan procedure is generally promising. A variety of complications can occur over time and require additional monitoring and procedures.

Failure of the circulation system created by the Fontan procedure might make a heart transplant necessary.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Tricuspid atresia and Learn More about Diseases

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome

Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome

Noonan syndrome

Restless legs syndrome

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

Uterine Inflammation (Cervicitis)

Type 2 diabetes

Fibromyalgia

tricuspid atresia, ট্রাইকসপিড অ্যাট্রেসিয়া

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.