Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

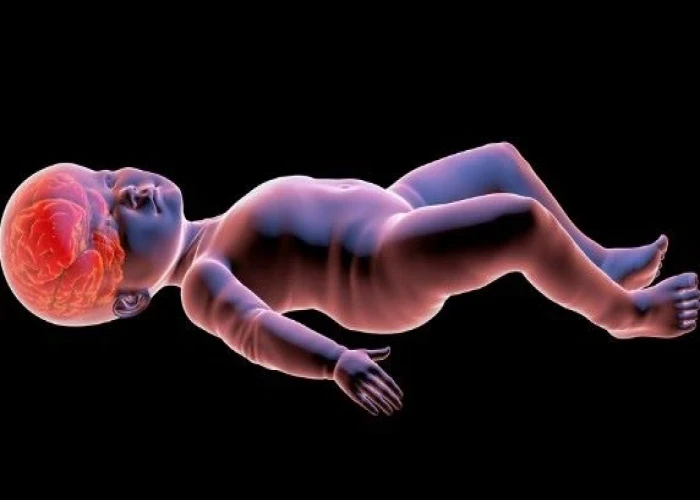

Pulmonary atresia

Pulmonary atresia is a rare congenital heart defect in which the pulmonary valve does not form properly, blocking blood flow from the right ventricle of the heart to the lungs. This leads to a lack of oxygen in the blood and can cause cyanosis (blue-tinted skin) in newborns.

There are different forms of pulmonary atresia, depending on the severity and location of the blockage. In some cases, there may be a small opening in the valve that allows some blood to flow to the lungs, while in others, the valve is completely blocked.

Treatment for pulmonary atresia typically involves surgery to create a pathway for blood to flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries. This may involve the use of a shunt or a conduit to reroute blood flow, or a surgical procedure to open the pulmonary valve.

In some cases, additional surgeries or procedures may be necessary to further improve blood flow and oxygenation. Children with pulmonary atresia may require ongoing monitoring and care from a pediatric cardiologist and other specialists to manage the condition and prevent complications.

While pulmonary atresia can be a serious and potentially life-threatening condition, advances in medical technology and surgical techniques have greatly improved the prognosis for affected individuals. With proper treatment and ongoing care, many children with pulmonary atresia are able to live healthy and active lives.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Blue skin (cyanosis)

- Brown skin

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Fatigue (Tiredness)

- Blue lips (cyanosis)

Disease Causes

Pulmonary atresia

There's no known cause of pulmonary atresia. To understand how pulmonary atresia occurs, it may be helpful to know how the heart works.

How the heart works

The heart is divided into four hollow chambers, two on the right and two on the left. In performing its basic job — pumping blood throughout the body — the heart uses its left and right sides for different tasks.

The right side of the heart moves blood to the lungs through vessels called pulmonary arteries. In the lungs, blood picks up oxygen then returns to the heart's left side through the pulmonary veins. The left side of the heart then pumps the blood through the aorta and out to the rest of the body to supply the body with oxygen.

Blood moves through the heart in one direction through valves that open and close as the heart beats. The valve that allows blood out of the heart and into the lungs to pick up oxygen is called the pulmonary valve.

In pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve doesn't develop properly, preventing it from opening. Blood can't flow from the right ventricle to the lungs.

Before birth, the irregular valve isn't life-threatening, because the placenta provides oxygen for the baby instead of the lungs. Blood entering the right side of the baby's heart passes through a hole (foramen ovale) between the top chambers of the baby's heart, so the oxygen-rich blood can be pumped out to the rest of the baby's body through the aorta.

After birth, the lungs are supposed to provide oxygen to the body. In pulmonary atresia, without a working pulmonary valve, blood must find another route to reach the baby's lungs. The foramen ovale usually shuts soon after birth, but it may stay open in pulmonary atresia.

Newborn babies also have a temporary connection (ductus arteriosus) between the aorta and the pulmonary artery. This passage allows some of the oxygen-poor blood to travel to the lungs, where it can pick up oxygen to supply the baby's body. The ductus arteriosus typically closes soon after birth, but it can be kept open with medications.

Sometimes, there may be a second hole in the tissue that separates the main pumping chambers of the baby's heart. This hole is a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

The VSD allows a pathway for blood to pass through the right ventricle into the left ventricle. Children with pulmonary atresia and a VSD often have additional problems with the lungs and the arteries that bring blood to the lungs.

If there's no VSD, the right ventricle receives little blood flow before birth and often doesn't develop fully. This is a condition called pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA/IVS).

Disease Prevents

Pulmonary atresia

Because the exact cause of pulmonary atresia is unknown, it may not be possible to prevent it. However, some things can be done before or during pregnancy to help reduce a baby's overall risk of congenital heart defects, such as:

- Control chronic medical conditions. If you have diabetes, keeping your blood sugar in check can reduce the risk of heart defects. If you have other chronic conditions, such as high blood pressure or epilepsy, that require the use of medications, discuss the risks and benefits of these drugs with your health care provider.

- Don't smoke. Smoking cigarettes during pregnancy may increase the risk of heart defects in a baby.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Obesity increases the risk of having a baby with a congenital heart defect.

- Get a German measles (rubella) vaccine. German measles during pregnancy may affect a baby's heart development. Being vaccinated before becoming pregnant likely eliminates this risk. However, no link has been shown between rubella and the development of pulmonary atresia.

Disease Treatments

A baby will need urgent medical attention once pulmonary atresia symptoms develop. The choice of surgeries or procedures depends on the severity of the child's condition.

Medications

Medication may be given through an IV to help prevent the closure of the natural connection (ductus arteriosus) between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. This is not a permanent treatment for pulmonary atresia, but it gives health care providers more time to determine what type of surgery or procedure might be best for the child.

Surgery or other procedures

Sometimes, pulmonary atresia repairs can be done using a long, thin tube (catheter) inserted into a large vein in a baby's groin and threaded up to the heart. Catheter-based procedures for pulmonary atresia include:

- Balloon atrial septostomy. A balloon is used to enlarge the natural hole (foramen ovale) in the wall between the upper two chambers of the heart. This hole usually closes shortly after birth. Making the hole larger increases the amount of blood available to travel to the lungs.

- Stent placement. A health care provider may place a rigid tube (stent) in the natural connection between the aorta and pulmonary artery (ductus arteriosus). This opening also usually closes soon after birth. Keeping it open allows blood to travel to the lungs.

Babies with pulmonary atresia often require a series of heart surgeries over time. The type of heart surgery needed will depend on the size of the child's right ventricle and pulmonary artery. Some examples include:

- Shunting. Creating a bypass (shunt) from the main blood vessel leading out of the heart (aorta) to the pulmonary arteries allows for adequate blood flow to the lungs. However, babies usually outgrow this shunt within a few months.

- Glenn procedure. In this surgery, one of the large veins that returns blood to the heart is connected directly to the pulmonary artery instead. Another large vein continues to provide blood to the right side of the heart, which pumps it through the surgically repaired pulmonary valve. This can help the right ventricle grow larger.

- Fontan procedure. If the right ventricle remains too small to be useful, surgeons may use this procedure to create a pathway that allows most, if not all, of the blood coming to the heart to flow directly into the pulmonary artery.

- Heart transplant. In some cases, the heart is too damaged to repair and a heart transplant may be necessary.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Pulmonary atresia and Learn More about Diseases

Foreign Body in eye

Noonan syndrome

TEN

Broken collarbone

Cardiomyopathy

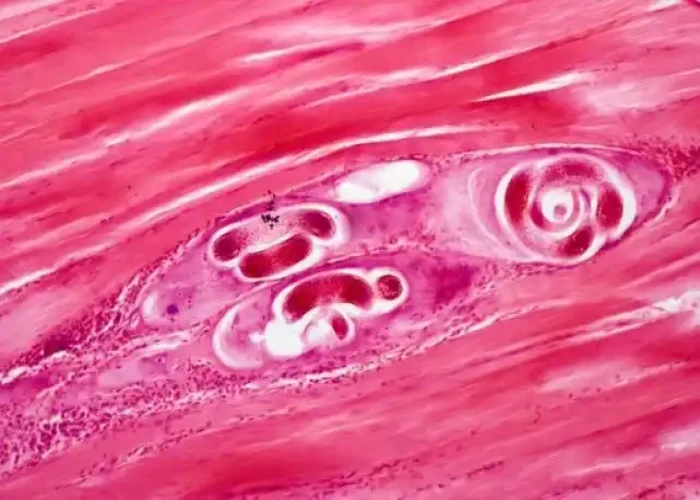

Trichinosis

Carcinoma of unknown primary

Broken wrist

pulmonary atresia, পালমোনারি অ্যাট্রেসিয়া

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.