Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic respiratory disease that makes it difficult to breathe. It is often caused by long-term exposure to irritants such as cigarette smoke, air pollution, or workplace dust and chemicals. COPD is a progressive disease that worsens over time and can lead to significant disability and reduced quality of life.

The most common symptoms of COPD include:

- Shortness of breath, especially during physical activity

- Wheezing or a whistling sound when breathing

- Chronic cough, often with mucus production

- Chest tightness or discomfort

- Fatigue and lack of energy

- Recurring respiratory infections

Diagnosis of COPD typically involves a physical exam, lung function tests, and imaging tests such as X-rays or CT scans. Treatment for COPD may include medications such as bronchodilators or corticosteroids, which can help improve breathing and reduce inflammation in the lungs. Oxygen therapy may also be necessary for people with severe COPD. In addition, pulmonary rehabilitation programs that include exercise, breathing techniques, and education about COPD management can help improve symptoms and quality of life.

Prevention of COPD involves avoiding exposure to irritants such as cigarette smoke, air pollution, and workplace chemicals. If you smoke, quitting smoking is the most important thing you can do to prevent or slow the progression of COPD. Vaccinations against respiratory infections such as the flu and pneumonia can also help reduce the risk of exacerbations in people with COPD.

COPD is a serious and life-changing disease, but with proper management, many people with COPD are able to lead active and fulfilling lives. If you have symptoms of COPD, it is important to see a healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Chest tightness

- Cough, chest tightness, wheezing or shortness of breath

- Chronic cough

- Recurrent respiratory infections

- Decreased energy

- Weight loss

- Swollen leg

- Swollen neck

Disease Causes

COPD

The main cause of COPD in developed countries is tobacco smoking. In the developing world, COPD often occurs in people exposed to fumes from burning fuel for cooking and heating in poorly ventilated homes.

Only some chronic smokers develop clinically apparent COPD, although many smokers with long smoking histories may develop reduced lung function. Some smokers develop less common lung conditions. They may be misdiagnosed as having COPD until a more thorough evaluation is performed.

How your lungs are affected

Air travels down your windpipe (trachea) and into your lungs through two large tubes (bronchi). Inside your lungs, these tubes divide many times — like the branches of a tree — into many smaller tubes (bronchioles) that end in clusters of tiny air sacs (alveoli).

The air sacs have very thin walls full of tiny blood vessels (capillaries). The oxygen in the air you inhale passes into these blood vessels and enters your bloodstream. At the same time, carbon dioxide — a gas that is a waste product of metabolism — is exhaled.

Your lungs rely on the natural elasticity of the bronchial tubes and air sacs to force air out of your body. COPD causes them to lose their elasticity and over-expand, which leaves some air trapped in your lungs when you exhale.

Causes of airway obstruction

Causes of airway obstruction include:

- Emphysema. This lung disease causes destruction of the fragile walls and elastic fibers of the alveoli. Small airways collapse when you exhale, impairing airflow out of your lungs.

- Chronic bronchitis. In this condition, your bronchial tubes become inflamed and narrowed and your lungs produce more mucus, which can further block the narrowed tubes. You develop a chronic cough trying to clear your airways.

Cigarette smoke and other irritants

In the vast majority of people with COPD, the lung damage that leads to COPD is caused by long-term cigarette smoking. But there are likely other factors at play in the development of COPD, such as a genetic susceptibility to the disease, because not all smokers develop COPD.

Other irritants can cause COPD, including cigar smoke, secondhand smoke, pipe smoke, air pollution, and workplace exposure to dust, smoke or fumes.

Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency

In about 1% of people with COPD, the disease results from a genetic disorder that causes low levels of a protein called alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAt). AAt is made in the liver and secreted into the bloodstream to help protect the lungs. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency can cause liver disease, lung disease or both.

For adults with COPD related to AAt deficiency, treatment options include those used for people with more-common types of COPD. In addition, some people can be treated by replacing the missing AAt protein, which may prevent further damage to the lungs.

Disease Prevents

COPD

Unlike some diseases, COPD typically has a clear cause and a clear path of prevention, and there are ways to slow the progression of the disease. The majority of cases are directly related to cigarette smoking, and the best way to prevent COPD is to never smoke — or to stop smoking now.

If you're a longtime smoker, these simple statements may not seem so simple, especially if you've tried quitting — once, twice or many times before. But keep trying to quit. It's critical to find a tobacco cessation program that can help you quit for good. It's your best chance for reducing damage to your lungs.

Occupational exposure to chemical fumes and dusts is another risk factor for COPD. If you work with these types of lung irritants, talk to your supervisor about the best ways to protect yourself, such as using respiratory protective equipment.

Here are some steps you can take to help prevent complications associated with COPD:

- Quit smoking to help reduce your risk of heart disease and lung cancer.

- Get an annual flu vaccination and regular vaccination against pneumococcal pneumonia to reduce your risk of or prevent some infections.

- Talk to your doctor if you feel sad or helpless or think that you may be experiencing depression.

Disease Treatments

Many people with COPD have mild forms of the disease for which little therapy is needed other than smoking cessation. Even for more advanced stages of disease, effective therapy is available that can control symptoms, slow progression, reduce your risk of complications and exacerbations, and improve your ability to lead an active life.

Quitting smoking

The most essential step in any treatment plan for COPD is to quit all smoking. Stopping smoking can keep COPD from getting worse and reducing your ability to breathe. But quitting smoking isn't easy. And this task may seem particularly daunting if you've tried to quit and have been unsuccessful.

Talk to your doctor about nicotine replacement products and medications that might help, as well as how to handle relapses. Your doctor may also recommend a support group for people who want to quit smoking. Also, avoid secondhand smoke exposure whenever possible.

Medications

Several kinds of medications are used to treat the symptoms and complications of COPD. You may take some medications on a regular basis and others as needed.

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators are medications that usually come in inhalers — they relax the muscles around your airways. This can help relieve coughing and shortness of breath and make breathing easier. Depending on the severity of your disease, you may need a short-acting bronchodilator before activities, a long-acting bronchodilator that you use every day or both.

Examples of short-acting bronchodilators include:

- Albuterol (ProAir HFA, Ventolin HFA, others)

- Ipratropium (Atrovent HFA)

- Levalbuterol (Xopenex)

Examples of long-acting bronchodilators include:

- Aclidinium (Tudorza Pressair)

- Arformoterol (Brovana)

- Formoterol (Perforomist)

- Indacaterol (Arcapta Neoinhaler)

- Tiotropium (Spiriva)

- Salmeterol (Serevent)

- Umeclidinium (Incruse Ellipta)

Inhaled steroids

Inhaled corticosteroid medications can reduce airway inflammation and help prevent exacerbations. Side effects may include bruising, oral infections and hoarseness. These medications are useful for people with frequent exacerbations of COPD. Examples of inhaled steroids include:

- Fluticasone (Flovent HFA)

- Budesonide (Pulmicort Flexhaler)

Combination inhalers

Some medications combine bronchodilators and inhaled steroids. Examples of these combination inhalers include:

- Fluticasone and vilanterol (Breo Ellipta)

- Fluticasone, umeclidinium and vilanterol (Trelegy Ellipta)

- Formoterol and budesonide (Symbicort)

- Salmeterol and fluticasone (Advair HFA, AirDuo Digihaler, others)

Combination inhalers that include more than one type of bronchodilator also are available. Examples of these include:

- Aclidinium and formoterol (Duaklir Pressair)

- Albuterol and ipratropium (Combivent Respimat)

- Formoterol and glycopyrrolate (Bevespi Aerosphere)

- Glycopyrrolate and indacaterol (Utibron)

- Olodaterol and tiotropium (Stiolto Respimat)

- Umeclidinium and vilanterol (Anoro Ellipta)

Oral steroids

For people who experience periods when their COPD becomes more severe, called moderate or severe acute exacerbation, short courses (for example, five days) of oral corticosteroids may prevent further worsening of COPD. However, long-term use of these medications can have serious side effects, such as weight gain, diabetes, osteoporosis, cataracts and an increased risk of infection.

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors

A medication approved for people with severe COPD and symptoms of chronic bronchitis is roflumilast (Daliresp), a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor. This drug decreases airway inflammation and relaxes the airways. Common side effects include diarrhea and weight loss.

Theophylline

When other treatment has been ineffective or if cost is a factor, theophylline (Elixophyllin, Theo-24, Theochron), a less expensive medication, may help improve breathing and prevent episodes of worsening COPD. Side effects are dose related and may include nausea, headache, fast heartbeat and tremor, so tests are used to monitor blood levels of the medication.

Antibiotics

Respiratory infections, such as acute bronchitis, pneumonia and influenza, can aggravate COPD symptoms. Antibiotics help treat episodes of worsening COPD, but they aren't generally recommended for prevention. Some studies show that certain antibiotics, such as azithromycin (Zithromax), prevent episodes of worsening COPD, but side effects and antibiotic resistance may limit their use.

Lung therapies

Doctors often use these additional therapies for people with moderate or severe COPD:

- Oxygen therapy. If there isn't enough oxygen in your blood, you may need supplemental oxygen. There are several devices that deliver oxygen to your lungs, including lightweight, portable units that you can take with you to run errands and get around town.

- Some people with COPD use oxygen only during activities or while sleeping. Others use oxygen all the time. Oxygen therapy can improve quality of life and is the only COPD therapy proved to extend life. Talk to your doctor about your needs and options.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation program. These programs generally combine education, exercise training, nutrition advice and counseling. You'll work with a variety of specialists, who can tailor your rehabilitation program to meet your needs.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation after episodes of worsening COPD may reduce readmission to the hospital, increase your ability to participate in everyday activities and improve your quality of life. Talk to your doctor about referral to a program.

In-home noninvasive ventilation therapy

Evidence supports in-hospital use of breathing devices such as bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), but some research now supports the benefit of its use at home. A noninvasive ventilation therapy machine with a mask helps to improve breathing and decrease retention of carbon dioxide (hypercapnia) that may lead to acute respiratory failure and hospitalization. More research is needed to determine the best ways to use this therapy.

Managing exacerbations

Even with ongoing treatment, you may experience times when symptoms become worse for days or weeks. This is called an acute exacerbation, and it may lead to lung failure if you don't receive prompt treatment.

Exacerbations may be caused by a respiratory infection, air pollution or other triggers of inflammation. Whatever the cause, it's important to seek prompt medical help if you notice a sustained increase in coughing or a change in your mucus, or if you have a harder time breathing.

When exacerbations occur, you may need additional medications (such as antibiotics, steroids or both), supplemental oxygen or treatment in the hospital. Once symptoms improve, your doctor can talk with you about measures to prevent future exacerbations, such as quitting smoking; taking inhaled steroids, long-acting bronchodilators or other medications; getting your annual flu vaccine; and avoiding air pollution whenever possible.

Surgery

Surgery is an option for some people with some forms of severe emphysema who aren't helped sufficiently by medications alone. Surgical options include:

- Lung volume reduction surgery. In this surgery, your surgeon removes small wedges of damaged lung tissue from the upper lungs. This creates extra space in your chest cavity so that the remaining healthier lung tissue can expand and the diaphragm can work more efficiently. In some people, this surgery can improve quality of life and prolong survival.

- Endoscopic lung volume reduction ― a minimally invasive procedure ― has recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat people with COPD. A tiny one-way endobronchial valve is placed in the lung, allowing the most damaged lobe to shrink so that the healthier part of the lung has more space to expand and function.

- Lung transplant. Lung transplantation may be an option for certain people who meet specific criteria. Transplantation can improve your ability to breathe and to be active. However, it's a major operation that has significant risks, such as organ rejection, and youꞌll need to take lifelong immune-suppressing medications.

- Bullectomy. Large air spaces (bullae) form in the lungs when the walls of the air sacs (alveoli) are destroyed. These bullae can become very large and cause breathing problems. In a bullectomy, doctors remove bullae from the lungs to help improve air flow.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

COPD and Learn More about Diseases

Botulism

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs)

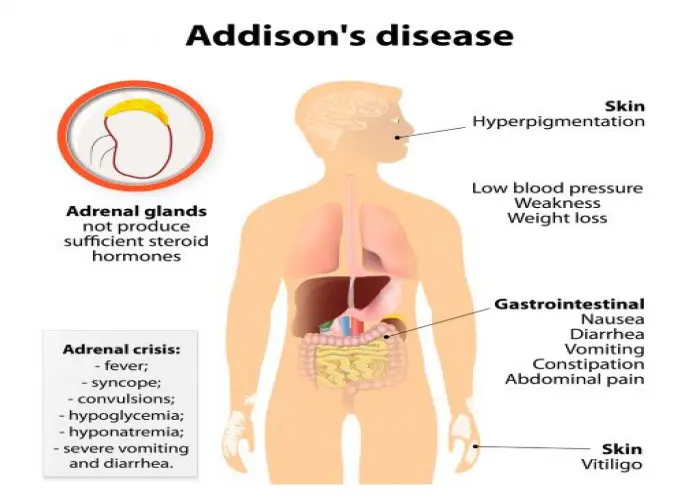

Addison's disease

Pruritus Vulva

Chest pain

Group B strep disease

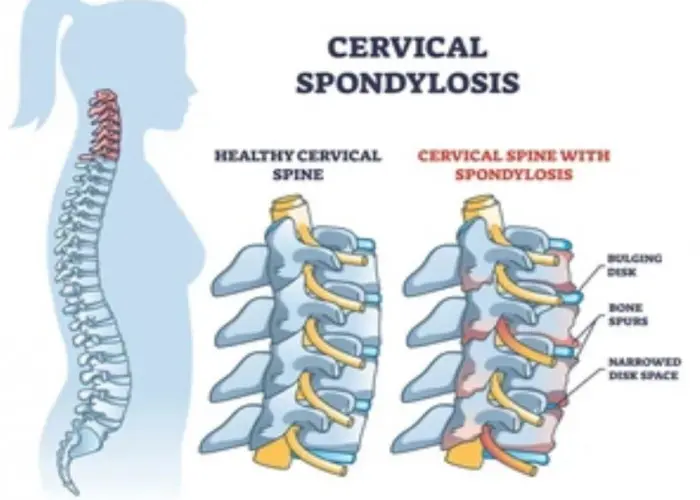

Cervical spondylosis

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD, COPD symptoms, ক্রনিক অবস্ট্রাকটিভ পালমোনারি ডিজিজ, সিওপিডি

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.