Welcome

Welcome

“May all be happy, may all be healed, may all be at peace and may no one ever suffer."

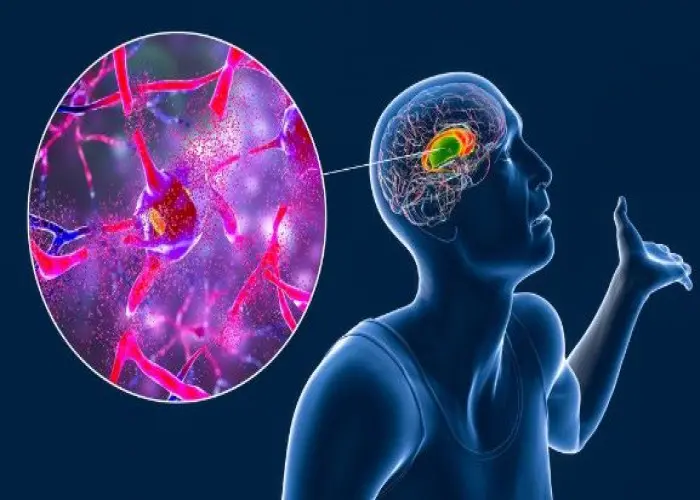

Hunter syndrome

Hunter syndrome, also known as mucopolysaccharidosis type II (MPS II), is a rare genetic disorder that affects the body's ability to break down complex sugars. The disorder is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme iduronate-2-sulfatase, which is needed to break down certain molecules in the body.

As a result, these molecules accumulate in the body's tissues and organs, leading to a wide range of symptoms. Hunter syndrome is an X-linked disorder, meaning it primarily affects males. Females can be carriers of the gene but typically do not develop the disorder.

Symptoms of Hunter syndrome can vary widely and can include physical symptoms such as coarse facial features, enlarged liver and spleen, joint stiffness, and respiratory problems. Other symptoms may include developmental delays, behavioral problems, and intellectual disability.

There is currently no cure for Hunter syndrome, but there are treatments available that can help manage the symptoms of the disorder. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) is the main treatment for Hunter syndrome, which involves regular infusion of the missing enzyme to help break down the complex sugars in the body. Other treatments may include surgery to remove excess fluid from the brain or other affected organs, or supportive therapies to manage the symptoms of the disorder.

It is important for individuals with Hunter syndrome to receive regular medical care from a healthcare provider who specializes in treating this disorder. Genetic counseling may also be recommended for individuals with a family history of Hunter syndrome or other genetic disorders.

Research Papers

Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Broad nose

- Delayed development, such as late walking or talking

- White skin growths that resemble pebbles

- A distended abdomen, as a result of enlarged internal organs

- Abnormal bone size or shape and other skeletal irregularities

- Joint stiffness

- Diarrhea

- Hoarse voice

- Large head

- Involuntary jerking or writhing movements (chorea)

Disease Causes

Hunter syndrome

Hunter syndrome develops when a defective chromosome is inherited from the child's mother.

Because of that defective chromosome, an enzyme that's needed to break down complex sugar molecules is missing or malfunctioning. Without this enzyme, massive amounts of these complex sugar molecules collect in the cells, blood and connective tissues, causing permanent and progressive damage.

Disease Prevents

Hunter syndrome

Hunter syndrome is a genetic disorder. Talk to your doctor or a genetic counselor if you're thinking about having children and you or any members of your family have a genetic disorder or a family history of genetic disorders.

If you think you might be a carrier, genetic tests are available. If you already have a child with Hunter syndrome, you may wish to seek the advice of a doctor or genetic counselor before you have more children.

Disease Treatments

Prenatal testing of the fluid that surrounds the baby or of a tissue sample from the placenta can verify if your unborn child carries a copy of the defective gene or is affected with the disorder.

Relief for respiratory complications

Removal of tonsils and adenoids can open up your child's airway and help relieve sleep apnea. But as the disease progresses, tissues continue to thicken and these problems can come back.

Breathing devices that use air pressure to keep the airway open — such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) devices — can help with upper airway obstructions and sleep apnea. Keeping your child's airway open can also help avoid low blood oxygen levels.

Addressing heart complications

Your child's doctor will want to watch closely for cardiovascular complications, such as high blood pressure, a heart murmur and leaky heart valves. If your child has severe cardiovascular problems, your doctor may recommend surgery to replace heart valves.

Treatment for skeletal and connective tissue problems

Because most children with Hunter syndrome don't heal well and often have complications after surgery, options are limited for addressing skeletal and connective tissue complications. For example, surgery to stabilize the spine using internal hardware is difficult when bones are fragile.

Your child's joint flexibility can be improved with physical therapy, which helps address stiffness and maintain function. But physical therapy can't stop the progressive decline of joint motion. Your child may eventually need to use a wheelchair because of pain and limited stamina.

Surgery can repair hernias, but because of weakness in connective tissues, results usually aren't ideal. The procedure often needs to be repeated. One option is to manage your child's hernias with supportive trusses rather than surgery because of the risks of anesthesia and surgery.

Managing neurological complications

Problems associated with the buildup of fluid and tissue around the brain and spinal cord are difficult to address because of the inherent risks in treating these parts of the body.

Your child's doctor may recommend surgery to drain excess fluids or remove built-up tissue. If your child has seizures, your doctor may prescribe anticonvulsant medications.

Managing behavioral problems

If your child develops abnormal behavior as a result of Hunter syndrome, providing a safe home environment is one of the most important ways you can manage this challenge. Treating behavior problems with medications has had limited success because most medications have side effects that can worsen other complications of the disease, such as respiratory problems.

Addressing sleep issues

The sleep patterns of a child with Hunter syndrome can become more and more disorganized. Medications including sedatives and especially melatonin can improve sleep.

Keeping a strict bedtime schedule and making sure your child sleeps in a well-darkened room also can help. In addition, creating a safe environment in your child's bedroom — putting the mattress on the floor, padding the walls, removing all hard furniture, placing only soft, safe toys in the room — may help you rest easier.

Emerging treatments

Some treatments have shown potential for slowing the disease's progress and lessening its severity, but long-term effects are unknown.

- Enzyme therapy. This Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment uses man-made or genetically engineered enzymes to replace your child's missing or defective enzymes and ease the disease symptoms. This treatment is given once a week through an intravenous (IV) line.

- Given early enough, enzyme replacement therapy may delay or prevent some of the symptoms of Hunter syndrome. It's unclear, however, if the improvements seen with this therapy are significant enough to raise quality of life for people with the disease. In addition, benefits in thinking and intelligence haven't been seen with enzyme replacement therapy.

- Serious allergic reactions can occur during enzyme replacement therapy. Other possible side effects include a headache, fever and skin reactions. Side effects may lessen over time or with a dose adjustment, however.

- Stem cell transplant. This procedure infuses healthy blood stem cells into your child's body with the hope that the new cells will create the missing or defective enzyme. However, treatment results have been mixed and more research is needed.

- Gene therapy. Replacing the chromosome responsible for producing the missing enzyme could theoretically cure Hunter syndrome, but much more research needs to be done before such a therapy might be available.

Disease Diagnoses

Disease Allopathic Generics

Disease Ayurvedic Generics

Disease Homeopathic Generics

Disease yoga

Hunter syndrome and Learn More about Diseases

Truncus arteriosus

Ocular rosacea

Wilms' tumor

Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea

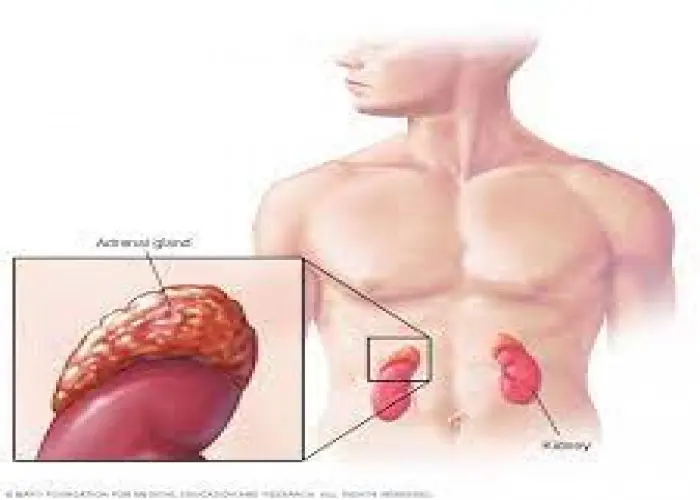

Benign adrenal tumors

Prostatitis

Huntington's disease

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

hunter syndrome, হান্টার সিনড্রোম

To be happy, beautiful, healthy, wealthy, hale and long-lived stay with DM3S.